Back in the day (turn of the last century) there was no such thing as camera batteries or sound men. Men were men and cameras were hand cranked. As they had evolved from still cameras they were sort of still camera Gatling guns, capturing still frames as fast as you cared to crank. Somewhere past 14fps something magical happened and persistence of vision started to fuse the images so rather than a fast slide show it started to look like motion. So cameras were built to move one linear foot of film per two cranks, which meant if you cranked at “coffee grinder” speed you hit 60 feet per minute, which comes out to 16fps, just north of that 14fps effect. Cranking faster improved the persistence of vision thing, but producers didn’t like you blowing through all that expensive film, and besides there was really only one stock available and it was slow, about 24asa. Cranking faster meant less light per frame. Sometimes you cranked even less than 14fps to squeeze a bit more exposure out of it.

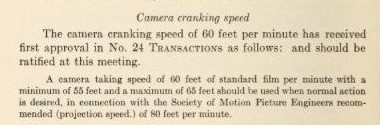

This is where it gets a little weird. Projectionists, who were also often hand cranking their projectors had a habit of cranking faster. Faster meant faster turnaround in seating, which meant more $ and even better persistence of vision without annoying flicker. Sure, action was sped up, but the whole thing was new, no one seemed to complain. In fact, by 1925 The Society Of Cinema Engineers (now known as SMPTE) had codified it recommending

60 feet per minute (16fps) for camera speeds and projecting at 80 feet per minute (21.3fps) seems weird now to pick a different speed for display from capture, but to review, faster cameras cost more money, and faster projectors made money, and after all, producers are paying for everything.

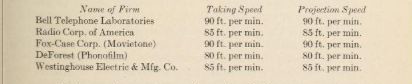

Anyway, someone decided it would be a great idea to add sound. How hard could it be? In fact, several companies tried to be the first to bring sound to the movies, hoping to capture the market. Funny thing is they all insisted on capturing at the same frame rate they displayed at. If you didn’t, the pitch would be all wrong and everybody would sound silly. And forget about music. Some picked 80 feet per minute (the already established speed for projection), some picked 85 feet per minute, and some picked 90 feet per minute. First one to get a working system was Warner Brothers Vitaphone. It was used in the 1927 “The Jazz Singer” which was the first feature length film with sync dialog and is considered the official start of the “Talkies.”

Western Electric’s Bell Telephone Laboratories (and their Vitaphone system) as well as other systems listed taking speed and projection speed (SMPTE 1927)

The Vitaphone engineers had picked 90 feet per minute, or 24fps as their capture and projection speed. If one of the others had been first, we easily could be shooting 21.33fps or 22.66fp as a standard today. So sometimes you get lucky.

Except the Vitaphone system was terrible. It sounded good but that’s all that could be said about it. The sound was recorded on 16″ disk records separate from the film. They could only be played 20-30 times before they were no good, and they could break, so you had to send lots of duplicate disks with each roll of film to the projectionist. A disk only covered one reel so every reel change you at to cue up another record. And synchronizing the needle with the head of the roll was a pain in the ass. And if you broke the film for some reason and spliced it back, everything past that point was out of sync. During recording, the camera had to be motor powered from the mains, and the disks had to be made in recording booth adjacent to the set. In fact it was such a bad system that it was abandoned 5 years after it was implemented. And it only lasted that long because all the theaters that wanted to have sound had bought into that technology and had these crazy phonograph contraptions connected to their projectors and weren’t eager in throwing them away just after having bought them. Movietone, which used technology that put the audio as an optical track on the film had many advantages, but it was a little late out of the gate. Because Vitaphone was first, the engineers of Movietone decided to match the Vitaphone frame rate.

“Originally we recorded at a film speed of 85 feet per minute. After Affiliation with the Western Electric Company, this was changed to 90 feet per minute in order to use the controlled motors already worked out and used in the Vitaphone system. There are a large number of both Vitaphone and Movietone installations scheduled and in operation, and sufficient apparatus is involved to make it impractical to change the present practice of sound reproducing. In connection with the Society’s standard, I have been unable to find any New York theater which is running film at 85 feet a minute; the present normal speed is 105 feet and on Sundays often 120 feet per minute is used in order to get in an extra show”

– Earl L Sponable, Technical Director, Fox-Case Corporation, New York City (“Some Techincal Apects of the Movietone” S.M.P.E. #31 September 1927, Page 458)

Soon enough Movietone lost ground as well, as technology changed but all subsequent sound systems stuck with the now established 24fps. So blame a sound man. Or thank him. Your choice.

One of the first sound men checking a Vitaphone recording with a microscope while recording. Sort of a human playback head. (page 308 from Transactions of S.M.P.E. August 1927) It turns out this man is George Groves.

Postscript: Now of course, we often mean 23.976 fps when we say 24 fps. This one we can’t blame on sound. 23.976 fps as a camera frame rate can be blamed on the introduction of color to standard-def television broadcasts in the 1950’s, and the death of film as a capture medium, and by extension the death of telecine as a post process.

When TV started, it did not match the 24 fps established by film. This is because engineers wanted to use the 60Hz cycle from our 110v 60Hz household power to drive frame rate. 60Hz meant 60 fields, or 30 frames per second, and was pretty easy to implement. Once color came along in the 1950’s they wanted a standard that would be backwards compatible with black and white TVs. Engineers could no longer use the 60hz rate of the household electricity to drive frame rates and keep the color and luminance signals to play nice so they settled on a very close one of 59.94hz. This resulted in a frame rate of 29.97 fps, from the previous 30 fps, something the black and white receivers would still work with.

Telecine: in order to get film onto TV you had to do a step called telecine. the film was played back and captured essentially by a video camera. Getting 24 fps to fit into 30 fps was done via a clever math solution by what is called 3:2 pulldown. There are two fields to a standard-def frame, and thus 60 fields per second, and 3:2 pulldown would use one film frame to make three fields (1.5 frames) of video. Then the second film frame made two fields (1 frame) of video, and the third frame made 3 fields again and so on. Doing this, 24 fps fits quite nicely into 30 fps broadcast. and anything shot 24 fps but shown at 29.97 fps system would look like it had been shot at 23.976 fps, even though the camera had been running at 24 fps, as anything that ran through the telecine went through a 01% slowdown to conform to the 29.97fps broadcast standard. Somewhere in the transition to High Definition 23.976 became codified as a standard, not only for broadcast, but a capture speed. As cameras more and more were digital and not film, they would choose 23.976 as the actual camera frame rate, rather than 24fps and expect the 0.1% slowdown to happen upon transfer from film to video, as had happened to film in telecine rooms. No telecine? no slowdown, which meant it had to be implemented in actual camera speed.

So, hate 23.976 fps? blame a Sound Man, color TV, the death of film and the whole accidental way we pick our standards.

For those interested in reading more, I highly recommend reading online records of the Journal of Society of Motion Picture Engineers, made available by the Media History Project. http://mediahistoryproject.org/technical/